Unrestrained capitalism, set against the backdrop of a neoliberal society so frequently marked by dehumanisation, has remained a central and enduring concern in the work of filmmaker Radu Jude (Bad Luck Banging or Loony Porn; Do Not Expect Too Much from the End of the World, Kontinental’ 25).

In a way, the Romanian filmmaker has been deconstructing something presented as real—the presumed sole and genuinely fair way to live—revealing it instead to be a myth: the capitalist myth that asserts a free economy, untouched by government or external intervention, will naturally regulate itself—as if guided by an invisible hand—leaving market forces alone to set prices. We’re told this leads to equal opportunity and a just sharing of wealth—something we’ve never actually seen, but are continually promised is just around the corner. Ah, naturally, as long as you have the right credentials—and as long as you accept the idea of endless economic growth, a notion capitalism insists is factual, even though it’s rooted in little more than belief.

And speaking of other myths, Jude has brought another into the spotlight with his latest film: Dracula. In his unmistakable style, he fuses the vampire legend with capitalism in its many forms—theme parks, tourist routes, libido-enhancing products, and more—delivering yet another audacious, conceptually brilliant work, once again selected for competition at the Locarno Film Festival.

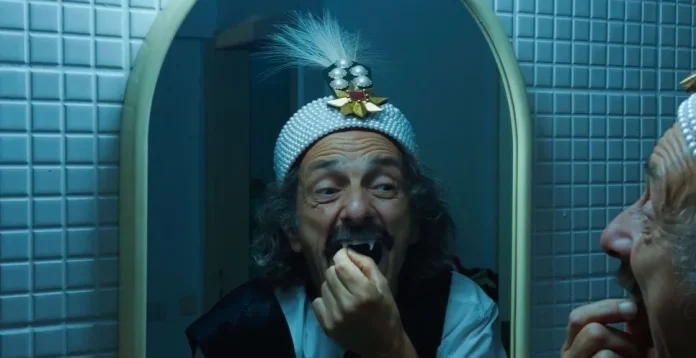

Jude’s Dracula, above all, is a critique of the film industry, of capitalist dynamics in post-auteur cinema, of cultural consumerism, and of the obsession with commercially viable content. To achieve this, he uses farce as his vehicle: a frustrated director desperate for commercial success (played by Adonis Tanța) turns to a fictional AI software (Dr. AI Judex 0.0) to generate a film packed with everything the audience allegedly craves. That means nudity, violence, plenty humour, frantic chase sequences—and blood. Lots of blood. For this creatively blocked filmmaker, cohesion or quality takes a backseat—here, cinema (and art itself) is reduced to a mere commodity, a product engineered by marketing labs to satisfy consumer demand.

At a sprawling 170 minutes, Dracula suffers from an exhausting repetition of a critique that is already fully formed and effectively condensed within the first 50 minutes. What follows is a festival of forms, styles and references—from historical analyses of Vlad the Impaler, to silent cinema and the era of Nosferatu, through Universal and Hammer’s interpretations of the creature, all the way to the present day and the TikTok-ification of life.

Artificial Intelligence—the latest (and perhaps final) tool of capitalism—is present not just as an alarmist mention in Jude’s chaotic script, but as the actual generator of many of the bizarre images that appear on screen.Indeed, the film opens with a sequence of such AI-generated images—16 in total—kicking off with Dracula declaring, “I’m Conde Dracula. Suck My Cock,” before launching into a cascade of nested narratives: an “inventive” exercise in AI-driven storytelling orchestrated by Jude, each frame shaped by the presumed desires of the “audience.” It’s a pointed reminder that those who fund films ultimately dictate what we see, hear, and consume—proving it’s market logic, not artistic vision, that steers every creative choice.

JJude is a provocateur at heart, wielding—often ruthlessly—every tool at his disposal to create a film that demands to be held, interrogated, and felt. Yet this repetition becomes exhausting, not only due to shifting rhythms and waning interest, but because the film never coheres into a solid object that sharpens its critique without alienating the viewer.

By handing creation over to AI, Jude criticises not only the market—he also attacks the very notion of the author. In his frustrated director, he illustrates the dilemma of the artist in a post-auteur world, where inspiration is replaced by algorithms. And by embracing the flaws and imperfections of this still-evolving technology, Jude also engages with another concern—one that even Scorsese finds troubling: the modern notion of “content,” a formless category that has erased the once-clear boundaries between cinema, television and home movies.

Operating entirely in parody, the director—uninterested in making a good film—delivers a grotesque commercial object that satirises itself. Yet in his relentless critique of the very process he’s enacting, Jude risks an endless loop. Dracula only coheres in the viewer’s mind, who, bombarded by images and sound, must sift through the chaos to grasp a message that could have been conveyed in far less than 170 minutes.

In the end, the audience isn’t just confronted with chaos—they’re forced to reconstruct meaning from the wreckage. But does a critique of excess justify—or even require—excess itself?